Table of contents

Introduction

During previous sessions, you learned how to write small functions and programs. Some of these programs required some user input. Until now, the only way to provide this input was by declaring it in the data section. This limits the different kinds of programs we can write: it is for example not possible to write a program that interacts with the user. During this session, you will learn how to interact with the operating system (OS) in order to interact with any hardware (e.g.: a mouse or keyboard).

The interactions with the operating system (through environment calls) are not part of the RISC-V specification and should be expected to be different on different platforms. For this reason, this exercise session can only be followed with RARS, not with the RISC-V Venus Simulator of Visual Studio. The Venus Simulator has different conventions for environment calls and does not implement all the environment calls used in this session. If you’re interested, you can take a look at the different environment calls supported by RARS and by the Venus simulator.

The operating system

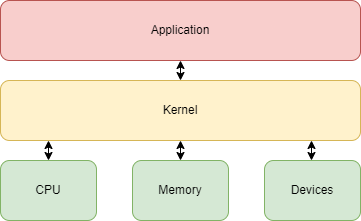

The OS is a piece of software that acts as a layer between programs and the hardware. It manages resources and provides an interface with a set of services such as input and output, and memory allocation. The kernel is the core of an OS. It controls all hardware resources with the aid of device drivers. The kernel acts as a layer for input and output requests from software and handles memory.

The OS also provides a form of security. Different program processes are isolated from each other when they are running at the same time. It is also not possible to overwrite the code of your OS.

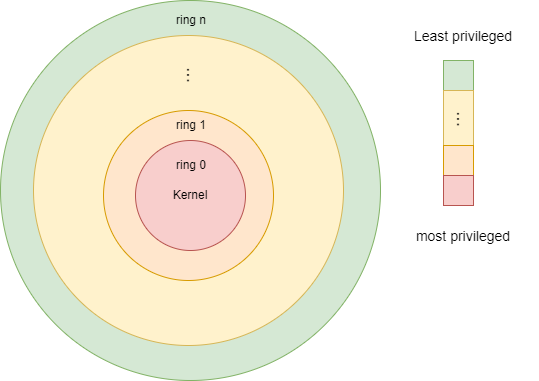

A Central Processing Unit (CPU) usually offers different modes. These modes have different levels of privileges. The most privileged mode has unrestricted access to all resources and instructions. Less privileged modes have a limited set of instructions that they can use and usually do not have direct access to resources. The amount of modes depends on the CPU’s architecture. The OS provides different services by using these modes: isolation of processes, scheduling of processes, communication between different processes, file systems…

RISC-V offers three privilege levels or modes:

-

Machine Mode: Machine mode is usually used during the boot of a machine. It has full access to the machine and the execution of any instruction is allowed.

-

Supervisor Mode: Supervisor mode allows the execution of most instructions, but not all of them. This mode is typically used when the kernel executes.

-

User Mode: The instructions that are allowed to be executed are limited in user mode. This mode is usually used during the execution of processes.

The RISC-V architecture only requires that machine mode is available on a CPU. Therefore, not all three modes are available on all CPUs.

The RARS emulator that you have been using during previous sessions does not only emulate a RISCV-V processor. It also simulates a tiny OS with its own set of services. All the programs that you assembled and executed in RARS were running on this OS in user mode. This means that it’s not possible by default to use all instructions of the RISC-V instruction set in RARS.

Requesting OS services

The OS offers different services to user programs. Such a service can be requested by invoking a system call (also named environment call in RISC-V). A system call is similar to a function call, but with two main differences. First, the level of privilege changes: the system call requests a service from the OS, which in turn takes control and fulfills the request in a different mode with a higher privilege level. Second, all registers are saved and restored by the OS, even the callee-saved registers (except for the register a0 that holds the return value of the system call). Therefore, there is no need to save callee-saved registers before a system call, contrary to a normal function call (cf. calling conventions).

A system call can be invoked by using the ecall instruction in RARS. The system call number has to be placed in a7 prior to invoking the ecall instruction. Some system calls take some input in specific registers and may produce some output. Following table lists a few examples of system calls that are provided by the OS of RARS. The full list is available on GitHub.

| Name | System call number (a7) | Description | Inputs | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PrintInt | 1 | Prints an integer |

a0 = integer to print | N/A |

ReadInt | 5 | Reads an int from input console | N/A |

a0 = the int |

Sbrk | 9 | Allocate heap memory |

a0 = amount of memory in bytes |

a0 = address to the allocated block |

Exit | 10 | Exits the program with code 0 | N/A | N/A |

Not every OS provides the same services through system calls. It depends on the OS (Windows, Linux, MacOS…), hardware, connected devices…

The following example shows how a system call can be used in RARS to print the int 666 to the RARS console. Integer 1 is loaded in a7 to use the PrintInt system call. This system call expects the int to print in a0.

| Example.asm | Output |

|---|---|

| |

Exercise 1

Write a user program that uses system calls to read two numbers from the user’s keyboard. Afterwards, print the sum of these two numbers. Remember that the full list of system calls in RARS can be found on GitHub.

Solution

.text

main:

li a7, 5

ecall

mv t0, a0

ecall

add a0, a0, t0

li a7, 1

ecall

The next example shows how a number, which was given by the user, can be printed to the RARS console. The program finishes with status code 0 at the end of its execution.

| Example.asm | Output |

|---|---|

| |

Exercise 2

Write a program which reads the name of the user from the keyboard. Afterwards, display a greeting message dialog with content “Welcome [name]”. Make sure your program does not crash when the user presses cancel or gives long inputs. Instead, display an appropriate error message dialog. Hint: Take a look at system calls 54, 55 and 59.

Everything placed in the

.datasection is placed in memory right after each other and in the same order that you put it. Remember that strings have an arbitrary length and simply end with a zero byte (0x00). This is because strings are simply an array of characters, 1 byte each. However, we also work with data that is organized in groups of bytes, such as a word. In a 32-bit architecture such as the one we are using here, a word contains 32 bits (4 bytes). Whenever you are using the instructionslw,swetc, you are instructing to access 4 bytes at a time. To speed up these accesses, the architecture relies on word-aligned memory. That means that thesewinstructions expect the address to be divisible by the word size (4). When you place a string before data that should be word aligned, you may encounter an error when you want to access this data. The solution to this error is an assembler directive to tell the assembler to align the next item in the data section according to the word boundary like this:.data str1: .string "Message 1" # May exceed word boundary str2: .string "Message 2" # May exceed word boundary .align 2 # Align next item to the word boundary heap: .space 100000

Solution

.data

input:

.string "Please input your name below "

welcome:

.string "Welcome "

error_msg:

.string "Input error"

user:

.space 10

.text

main:

la a0, input

la a1, user

# a1: address of username array

li a2, 10

li a7, 54

ecall # InputDialogString (read username)

# a1: status value

# with the bnez we check whether the status value was 0 (OK) or not: if not, we jump to the error handler

bnez a1, error

# if we get here (we did not jump away), we know that the status was OK, we don't need to worry about it anymore

la a0, welcome

la a1, user

# a1: address of username array (again)

li a7, 59

ecall # MessageDialogString (show welcome message)

b exit

error:

la a0, error_msg

li a1, 0

li a7, 55

ecall

exit:

li a7, 10

ecall

The heap - revisited

During the last session, you learned how to dynamically allocate memory on the heap. Dynamic allocation is required when data structures have to be allocated that can shrink or grow in size at runtime; it is not known prior to compilation how much memory should be allocated for these data structures.

In order to tackle this problem, a big chunk of memory was reserved in the .data section that could be used to dynamically request and allocate memory. We used register s9 to keep track of the next free memory location in the heap. A simple allocator function could be used to request memory from the heap and increase the address of the first free memory location with the amount of bytes that was requested:

.data

heap: .space 100000

.text

allocate_space: # Assume that s9 keeps track of the next free memory location in the heap

mv t0, a0 # The size to allocate is provided as an argument to the function

mv a0, s9 # Return old value of s9 as a pointer to the new allocated space

add s9, s9, t0 # Update the value of heap pointer in s9

ret

This approach has the following problems:

- We arbitrarily have to choose the size of the heap in the

.datasection. When this size is too small, the program may run out of heap memory too quick. Choosing this size too big may waste memory that is actually not required for the program. - We had to violate the RISC-V calling conventions in order to keep track of the next free memory location in the heap (

s9).

The OS to the rescue

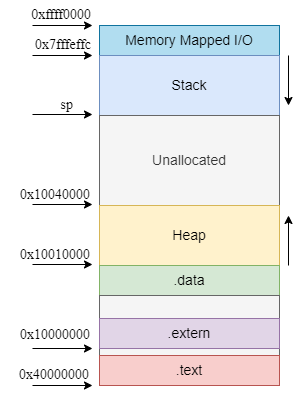

For every program that you run in RARS, a fixed address space is provided by the RARS OS for the program’s process. For 32bit RARS, the process layout is as follows:

The .text sections contains the program’s code. Every jump or branch that you write will land in this section. The .data section contains the global variables that you declared in advance. The heap and stack are both dynamic regions: their size can grow and shrink when required. The OS reserves just enough memory for the program to run. When the processes require more memory, more memory can dynamically be requested from the heap region, which is initially empty, through a system call. This is in contrast with our approach that reserved a heap in the .data section: we might have reserved a lot of bytes that the process would never even use or need, which would be a waste of memory.

Dynamically allocating memory

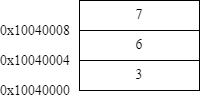

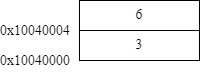

The RARS OS provides a system call sbrk (system call number 9) to dynamically request memory. When you request n bytes with sbrk, the OS will increase the heap region with n bytes towards the stack and returns an address, pointing inside the heap region, that can be used to store n bytes. This system call replaces the use of the simple allocator function. Following code snippet shows how sbrk can be used to dynamically allocate 8 bytes and store two integers in this newly allocated heap region.

.globl main

.text

main:

li a7, 9 # sbrk

li a0, 8 # allocate 8 bytes

ecall

li t0, 3

li t1, 6

sw t0, 0(a0) # store int 3

sw t1, 4(a0) # store int 6

Releasing allocated memory

It would not be efficient to keep increasing the heap when previously allocated memory is no longer in use; we have to free it. This allows to later on reuse this memory when more memory is again required. In the last exercise of previous session, you had to come up with an allocator that also allows to free previous allocated memory.

Releasing memory in RARS

It is possible to pass a negative integer to the sbrk system call in RARS. This could be used to free previously allocated memory. However, this would not always be sufficient to release any memory that you previously allocated. It only allows to free the last chunk of bytes that previously has been allocated through sbrk. Have a look at following example:

| Example.asm | Heap after allocation | Heap after free |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

Suppose you also want to free 3 from the heap, but would like to keep 6 on the heap. The only way to free it, is by passing -8 bytes to sbrk. This would however also free 6 and you would no longer be able to use it.

(De)allocating memory in C

One of the disadvantages of sbrk in RARS is that it is not possible to free any chunk of memory that you want. Another disadvantage is that system calls, like sbrk, have some overhead. A system call consists of multiple instructions that have to be executed. The kernel has to manage the allocation of memory, which will require a switch from user mode to another mode with a higher privilege level.

Programming languages sometimes offer complex functions to handle the (de)allocation of memory. In C, this functionality is provided by malloc and free (provided in stdlib.h). malloc is a function which allows to dynamically allocate a number of bytes. It returns a pointer to the allocated memory. A pointer can be passed as an argument to free to free the memory that was previously allocated for the data the pointer is pointing to. Following code snippet shows how free and malloc can be used:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

struct person {

char *name;

int age;

};

int main() {

// allocate enough memory on the heap for a person

struct person *p = malloc(sizeof(struct person));

// check if malloc was able to allocate enough memory

if (p == 0) {

abort(); // abort the program, the allocation failed

}

p->name = "Dave";

p->age = 20;

// we no longer need 'p', so we free it

free(p);

}

Note that malloc may return a null pointer. This happens when it was unable to allocate the amount of requested bytes. Therefore, it is important to check whether malloc returned a null pointer or not.

Excursion: Allocating memory in Python

In Python the developer never has to manage memory themselves. Does this mean that Python needs no memory management?

Wrong: Python just hides most memory management from the developers to be more developer-friendly. However, behind the scenes, Python still has to manage its own memory. Let’s take a look at a Python code piece and how it is handled behind the scenes:

a = []

a.append(1)

a.append(2)

print(a)

One very common Python implementation is CPython, a Python interpreter implemented in the C language. This means that you write programs in Python and execute them with a program that has itself been written (and compiled) in C. If you used Python before, the chances are high that you used CPython as it is the reference implementation for Python. The great thing is that CPython is fully open-source, so you can take a look at the source code on GitHub.

Now what exactly happens for our code above? There are too many details to discuss them here in-depth, but a very short explanation of an interpreter like CPython is this:

- Parse the program line by line, starting from the entry into the program

- For each line, interpret what is supposed to happen

- Execute the corresponding C function for this specific line of code

- Continue with 2 until the program is being exited (which, itself, is a C function

exitbeing called)

For the code above, we first create a list a = []. This will execute the C function PyList_New which creates a new list. It does several other things, but one important piece is this code part here:

op->ob_item = (PyObject **) PyMem_Calloc(size, sizeof(PyObject *));

if (op->ob_item == NULL) {

Py_DECREF(op);

return PyErr_NoMemory();

}

To create a new list, a function named PyMem_Calloc is called (see its implementation here). Obviously the code is more complex than our example code above since it has to handle a lot of edge cases and difficulties. But at the core of it, Python itself calls some malloc function (here called calloc), which internally will make a system call to get more memory if needed.

malloc and the

SBRKsystem call may seem unimportant, but no modern program can go without it, even if it looks to the end developer as if memory magically appears out of nowhere.

Interrupts and exceptions

Suppose you press a key on your keyboard which is connected to your computer. The OS has to be aware that a key has been pressed, in order to pass it on to an application. An OS is continuously executing different processes. It does not only wait and listen for these key-presses. Hence, an interrupt of the current process is required in order to handle the key-press. When such an interrupt takes place, a flag will be raised in order to alert the OS that an interrupt has been requested. The OS checks this flag when it has found the right moment. Following table lists the different kind of interrupts in RARS:

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | User software interrupt |

| 1 | Supervisor software interrupt |

| 2-3 | Reserved for future standard use |

| 4 | User timer interrupt |

| 5 | Supervisor timer interrupt |

| 6-7 | Reserved for future standard use |

| 8 | User external interrupt |

| 9 | Supervisor external interrupt |

| 10-15 | Reserved for future standard use |

| >= 16 | Reserved for platform use |

Exceptions are usually raised when something goes wrong in a faulty program. The execution of the program has to be halted and the error has to be resolved if possible. Exceptions have to be handled immediately. This is different from an interrupt; an OS will handle an interrupt as soon as possible. Exceptions are not only raised when something goes wrong; the ecall in RARS is a special kind of exception (see code 8-9 in following table) to handle system calls.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Instruction address misaligned |

| 1 | Instruction access fault |

| 2 | Illegal instruction |

| 3 | Breakpoint |

| 4 | Load address misaligned |

| 5 | Load access fault |

| 6 | Store/AMO address misaligned |

| 7 | Store/AMO access fault |

| 8 | Environment call from U-mode |

| 9 | Environment call from S-mode |

| 10-11 | Reserved for future standard use |

| 12 | Instruction page fault |

| 13 | Load page fault |

| 14 | Reserved for future standard use |

| 15 | Store/AMO page fault |

| 16-23 | Reserved for future standard use |

| 24-31 | Reserved for custom use |

| 32-47 | Reserved for future standard use |

| 48-63 | Reserved for custom use |

| >= 64 | Reserved for future standard use |

Handling interrupts and exceptions

As mentioned before, an interrupt will be handled as soon as possible when the OS finds the right moment, while an exception has to be handled immediately. When an interrupt or exception occurs, a trap is raised.

A trap handler comes in action whenever a trap is raised. It’s a set of instructions (like a function) that deal with the interrupt or exception. The address of a trap handler is stored in a tvec (Trap Vector) register. The CPU jumps to the address of the trap handler and continues executing the instructions of the trap handler. Each mode has its own tvec register:

-

utvec: User Trap Vector (user mode) -

stvec: Supervisor Trap Vector (supervisor mode) -

mtvec: Machine Trap Vector (machine mode)

Trap handling is managed by Control Status Registers (CSRs), which are special purpose registers. The following CSRs contain information specific to trap handling:

-

ustatus: keeps track of and controls the current operating state of the CPU. -

utvec: Contains the base address of the user trap handler. The CPU will jump to this address when a trap should be handled in user mode. -

uscratch: A temporary scratch register that can be used by the user trap handler. Note that all normal registers must be restored after the trap handler: the trap handler might resume the execution of the program. However, it is not possible to temporarily backup these registers on the stack, because the stack pointer (sp) might be corrupted (point to a random or invalid place in memory). For instance,uscratchcan be used as a backup for a normal register! -

uepc: The user exception program counter contains the address of the instruction that caused the trap. This allows to jump back to the point where the trap was raised after the trap has been handled. -

ucause: This register contains the cause of the raised trap. This corresponds to the codes listed in previous tables. E.g.:ucausewill have value4in case of a load address was misaligned. -

utval: This register contains a bad address or the address of an illegal instruction when applicable. E.g.:utvalcontains the faulty address when a load access fault occurs, or the address of an illegal instruction when it was not valid. -

uip: The user interrupt pending register tells whether the trap was raised by an interrupt (1) or exception (0).

Traps are handled in machine mode by default in RISC-V. It is however possible to delegate the trap handling to another mode that has a lower privilege level. This can be done by using deleg registers. E.g.:

medelegcan be used to forward exceptions or interrupts from machine mode to the next privilege level andsedelegdelegates from supervisor mode to user mode.

Handling traps in RARS

It is not possible to use regular instructions to change the content of CSRs. Specific instructions should be used to read from or write values into these registers:

| Example usage | Description |

|---|---|

csrrc t0, fcsr, t1 | Atomic Read/Clear CSR: read from the CSR fcsr into t0 and clear bits of the CSR according to t1

|

csrrci t0, fcsr, 10 | Atomic Read/Clear CSR Immediate: read from the CSR fcsr into t0 and clear bits of fcsr according to a constant |

csrrs t0, fcsr, t1 | Atomic Read/Set CSR: read from the CSR fcsr into t0 and bitwise or t1 into the CSR |

csrrsi t0, fcsr, 10 | Atomic Read/Set CSR Immediate: read from the CSR fcsr into t0 and bitwise or a constant into the CSR |

csrrw t0, fcsr, t1 | Atomic Read/Write CSR: read from the CSR fcsr into t0 and write t1 into the CSR |

csrrwi t0, fcsr, 10 | Atomic Read/Write CSR Immediate: read from the CSR fcsr into t0 and write a constant into the CSR |

System call that are requested in user mode, are handled by the trap handler in supervisor mode in RARS. Therefore, we do not have access to the supervisor trap handler. It is however possible to add a custom trap handler in user mode. This requires that interrupts in user mode are enabled before the trap is raised. This can be done by changing the value of ustatus. Following example shows how a custom trap handler can be used:

.globl main

.text

handler:

csrrw a0, ucause, zero # Move ucause to a0 and zero to ucause

la t0, end

csrrw zero, uepc, t0 # move epc to success and return

uret # jumps to the address in uepc

main:

la t0, handler

csrrw zero, utvec, t0 # set utvec so it points to our custom trap handler

csrrsi zero, ustatus, 1 # set interrupt enable in use mode

lw t0, 1 # trigger trap (misaligned load, address isn't multiple of 4)

li a7, 10

ecall # exit (0)

end:

li a7, 93

ecall # exit (4)

The main function first loads the address of the custom trap handler in utvec and enables trap handing in user mode. Next, a misaligned load instruction is used to trigger the trap. The custom handler moves the cause of the trap to a0 and jumps to end. The instructions below end: exit the program with a status code that reflects the cause of the trap (a0).

Exercise 3

Write a custom user-mode exception handler. The exception handler should do nothing but jump over the faulting instruction. Make sure the handler does not modify any regular registers (Hint: use uscratch). Do not forget to enable custom trap handling in user mode (csrrsi zero, ustatus, 1) before triggering the trap.

Solution

.globl main

.text

handler:

csrrw zero, uscratch, t0 #back-up value of t0 in uscratch

csrrw t0, uepc, zero #read uepc (address of faulting instruction) in t0

addi t0, t0, 4 #add 4 to uepc to skip faulting instruction

csrrw zero, uepc, t0 #Move skip address to uepc

csrrw t0, uscratch, zero #Restore old t0 value

uret

main:

csrrsi zero, ustatus, 1 # set interrupt enable (only needed in RARS)

la t0, handler

csrrw zero, utvec, t0 # set utvec to address of custom exception handler

lw t0, 1 # trigger trap

li a7, 10

ecall # exit (0)

Exercise 4

Extend the handler from previous exercise so that it prints:

- The cause of the exception

- The address of the instruction that caused the exception

A possible output could be:

Exception with cause 4 occured at address 0x00400074

-- program is finished running (0) --

Make sure to restore all register values before returning from the trap handler. In theory, you could use the call stack for this purpose. However, the stack pointer itself might be misaligned. Using the stack pointer would then cause an additional exception within the handler. A better alternative is to reserve space in the data section to back-up registers. You will still need to load the initial address of this space into a register, so you will still need to use the uscratch register to back-up that specific register.

Solution

.globl main

.data

trapframe: .space 8 #Mini-trapframe that stores a0 - a7 during trap handler execution

print_str_1: .string "Exception with cause "

print_str_2: .string " occured at address "

.text

handler:

csrrw zero, uscratch, t0 #back-up value of t0 in uscratch

la t0, trapframe #Back up values a0 and a7 to our small trapframe

sw a0, (t0)

sw a7, 4(t0)

la a0, print_str_1 #Print first string

li a7, 4

ecall

csrrw a0, ucause, zero #Print exception cause

li a7, 1

ecall

la a0, print_str_2 #Print second string

li a7, 4

ecall

csrrw a0, uepc, zero #Print exception address as hexadecimal

li a7, 34

ecall

addi a0, a0, 4 #add 4 to uepc to skip faulting instruction

csrrw zero, uepc, a0 #Move skip address to uepc

lw a0, (t0) #Restore a0 and a7 from trapframe

lw a7, 4(t0)

csrrw t0, uscratch, zero #Restore old t0 value

uret

main:

csrrsi zero, ustatus, 1 # set interrupt enable (only needed in RARS)

la t0, handler

csrrw zero, utvec, t0 # set utvec to address of custom exception handler

lw t0, 1 # trigger trap

li a7, 10

ecall # exit (0)

Playing music

System calls can also be used in RARS to play music. The RARS OS interacts with the sound card of you system in order to play tones.

Exercise 5

Create a RARS program that plays musical notes using the RARS system calls MidiOut (number 31) and Sleep (number 32). Use the following skeleton as a starting point and proceed as follows:

- Read through the provided skeleton code. How is the music represented as a string?

- Read through the code for the provided function

next_tone_from_stringwhich converts a given string element into a MIDI tone value. Which values are returned in thea0anda1registers? How can they be used? - Implement

play_songby iterating over the null-terminated song string and making use of thenext_tone_from_stringandplay_tonehelper functions. Make sure to adhere to the calling conventions. - Now implement

play_toneby making use of system calls 31 (MIDI out) and 32 (sleep). Make sure to first read the documentation for system call 31 (MIDI out). How many parameters are required? Which parameters are provided as global constants in the code skeleton and which parameters vary depending on the music string?

.data

song: .string "CCisCCesC CCGGAAG FFEEDDC" #The song string itself.

# Any note (A-G) can be raised half a pitch (sharpened) with suffix is (e.g. Ais -> A sharp)

# Any note (A-G) can be lowered half a pitch (flattened) with suffix es (e.g. Des -> D flat)

# A space equals a rest

scale_base: .word 57 # leave this value unless you want to transpose the base scale

bpm: .word 100 # Beats per minute of the song

duration: .space 4 # Calculated in main (from bpm)

instrument: .word 1 # Change to whatever instrument you like

volume: .word 127 # Choose value between 0 and 127

.globl main

.text

# next_tone_from_string - begin

# Reads the first tone from a string of music letters

# a0 should contain the address of the string

# In a0 the tone number (which can be provided to play_tone) is returned

# In a1 the amount of bytes used from the input string is returned

# e.g. C -> 1 byte, Cis -> 3 bytes

next_tone_from_string:

li t0, 0x41 # A

mv t2, a0 # t2 now holds address of string

lb t1, 0(t2)

beq t1, t0, ret_A

li t0, 0x42

beq t1, t0, ret_B

li t0, 0x43

beq t1, t0, ret_C

li t0, 0x44

beq t1, t0, ret_D

li t0, 0x45

beq t1, t0, ret_E

li t0, 0x46

beq t1, t0, ret_F

li t0, 0x47

beq t1, t0, ret_G

li a0, 0

li a1, 1

ret

ret_A:

li a0, 12

j adjust

ret_B:

li a0, 13

j adjust

ret_C:

li a0, 3

j adjust

ret_D:

li a0, 5

j adjust

ret_E:

li a0, 7

j adjust

ret_F:

li a0, 8

j adjust

ret_G:

li a0, 10

j adjust

adjust:

lb t1, 1(t2) # See if we encounted sharp or flat

li t0, 0x65 # e

beq t0, t1, flat

li t0, 0x69 # i

beq t0, t1, sharp

li a1, 1

ret

sharp:

addi a0, a0, 1

li a1, 3

ret

flat:

addi a0, a0, -1

li a1, 3

ret

#next_tone_from_string end

# Plays the song given in a0

# a0 contains a pointer to the song string

# tip: Use the functions next_tone_from_string and play_tone to play all tones in the input string

play_song:

# TODO implement

# Plays the tone given in a0

# if a0 is zero, a pause is expected (of duration "duration")

# otherwise, play the tone with pitch a0 + scale_base (also with duration "duration")

play_tone:

# TODO implement

main:

li t0, 60000

lw t1, bpm

div t2, t0, t1 # 60000/bpm = ms delay

sw t2, duration, t3 # t2: duration of note/delay

la a0, song

jal play_song

li a7, 10

ecall

Solution

.data

song: .string "CCisCCesC CCGGAAG FFEEDDC" #The song string itself.

# Any note (A-G) can be raised half a pitch (sharpened) with suffix is (e.g. Ais -> A sharp)

# Any note (A-G) can be lowered half a pitch (flattened) with suffix es (e.g. Des -> D flat)

# A space equals a rest

scale_base: .word 57 #leave this value unless you want to transpose the base scale

bpm: .word 100 # Beats per minute of the song

duration: .space 4 # Calculated in main (from bpm)

instrument: .word 1 # Change to whatever instrument you like

volume: .word 127 # Choose value between 0 and 127

.globl main

.text

#next_tone_from_string - begin

# Reads the first tone from a string of music letters

# a0 should contain the address of the string

# In a0 the tone number (which can be provided to play_tone) is returned

# In a1 the amount of bytes used from the input string is returned

# e.g. C -> 1 byte, Cis -> 3 bytes

next_tone_from_string:

li t0, 0x41 #A

mv t2, a0 #t2 now holds address of string

lb t1, 0(t2)

beq t1, t0, ret_A

li t0, 0x42

beq t1, t0, ret_B

li t0, 0x43

beq t1, t0, ret_C

li t0, 0x44

beq t1, t0, ret_D

li t0, 0x45

beq t1, t0, ret_E

li t0, 0x46

beq t1, t0, ret_F

li t0, 0x47

beq t1, t0, ret_G

li a0, 0

li a1, 1

ret

ret_A:

li a0, 12

j adjust

ret_B:

li a0, 13

j adjust

ret_C:

li a0, 3

j adjust

ret_D:

li a0, 5

j adjust

ret_E:

li a0, 7

j adjust

ret_F:

li a0, 8

j adjust

ret_G:

li a0, 10

j adjust

adjust:

lb t1, 1(t2) #See if we encounted sharp or flat

li t0, 0x65 #e

beq t0, t1, flat

li t0, 0x69 #i

beq t0, t1, sharp

li a1, 1

ret

sharp:

addi a0, a0, 1

li a1, 3

ret

flat:

addi a0, a0, -1

li a1, 3

ret

#next_tone_from_string end

#Plays the song given in a0

# a0 contains a pointer to the song string

# tip: Use the functions next_tone_from_string and play_tone to play all tones in the input string

play_song:

addi sp, sp, -12

sw ra, 0(sp)

_ps_loop:

lb t0, 0(a0)

beqz t0, _end_song

sw a0, 4(sp)

jal next_tone_from_string

sw a1, 8(sp)

jal play_tone

lw a0, 4(sp)

lw t0, 8(sp)

add a0, t0, a0

j _ps_loop

_end_song:

lw ra, 0(sp)

addi sp, sp, 12

ret

#Plays the tone given in a0

#if a0 is zero, a pause is expected (of duration "duration")

#otherwise, play the tone with pitch $a0 + scale_base (also with duration "duration")

play_tone:

beqz a0, pause

lw t0, scale_base

add a0, a0, t0

lw a1, duration

lw a2, instrument

lw a3, volume

li a7, 33

ecall

ret

pause:

li a7, 32

lw a0, duration

ecall

ret

main:

li t0, 60000

lw t1, bpm

div t2, t0, t1 #60000/bpm = ms delay

sw t2, duration, t3 #t2: duration of note/delay

la a0, song

jal play_song

li a7, 10

ecall

Bonus - Exercise 6

Implement the - sign in the music string of this exercise to make notes sound longer. This would work as follows: C- B-- A would play C for 2 times the normal duration, B for 3 times the normal duration and A would be played as normal.